In a middle-school auditorium in Cranbrook, BC, Faye O’Neil guides students through an interactive educational activity called the Kairos Blanket Exercise. Blankets represent Indigenous land and are slowly taken away as the students role-play and re-enact history. When the activity is finished, O’Neil, an Aboriginal education coordinator and member of the Ktunaxa Nation, invites students to share their thoughts.

She recalls one response she got from a ninth grader. “A student put her hand up and said, ‘we already learned this in grade seven. I’m tired of having this stuff shoved down our throats.’”

This response was not unusual prior to the implementation of BC’s new curriculum for Kindergarten to Grade 12 in 2015, according to O’Neil. After a three-year trial that included feedback from teachers, the Ministry of Education implemented a curriculum that acknowledges the changing world and workforce. Among the many changes was the mandatory inclusion of Indigenous perspectives, culture, and history in every subject from language arts to math.

“This is untold history. This is the stuff they didn’t teach in history textbooks,” O’Neil says. “This is the truth. Now that we have the truth, how do we incorporate that into classrooms?”

First Steps

In 2007 educators began to include Indigenous perspectives in schools. The First Nations Education Steering Committee created and published the First Peoples Principles of Learning. One principle is “learning is embedded in memory, history, and story.” The Principles informed the design of English First Peoples courses and would later help shape the redesign of BC’s K–12 curriculum.

English First Peoples courses fulfill the Ministry of Education’s English requirement for Grades 10–12 and feature exclusively Indigenous content. All materials, including literature and film, are created by Indigenous peoples. Since 2008 many schools have begun to offer the course.

Elders from the Ktunaxa Nation, including O’Neil’s mother, frequently sit in on English First Peoples courses to answer students’ questions. O’Neil’s mother shares her experience as a Survivor of the Canadian Indian Residential School (IRS) system in classrooms across the Kootenays. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in 2008 with a mandate of engaging in “a multi-year process to listen to Survivors, communities, and others affected by the Residential School system.” The TRC describes Canada’s residential schools as institutions that “separated Aboriginal children from their families, in order to minimize and weaken family ties and cultural linkages.”

An Erased History

In 2015 the TRC published 94 recommendations, or Calls to Action, to advance reconciliation. This included the call for the development of “culturally appropriate curricula” for Grades K–12. Prior to the development of English First Peoples 10–12 and these calls to action, there was scarce mention of the IRS system in Canadian classrooms or in society at large.

Many Canadian citizens are still unaware of the existence of residential schools in Canada though, according to the TRC, the last one closed in 1996.

This is untold history. This is the stuff they didn’t teach in history textbooks. This is the truth.

Faye O’neil

“I don’t know if I was [angrier] at myself or at the system,” Darryl Penny, an elementary school teacher in Delta, says of not having known about residential schools until well into his teaching career. Penny has been a teacher for 20 years but did not learn about the existence of residential schools in Canada until 2010. He thinks that the Canadian government effectively hid or “erased” our shared history.

Penny says he wants his students to understand that they are “part of a bigger community.” He knows that Indigenous content is important but is not sure it is seen as a priority for some teachers as they adapt to the new curriculum. “Is it mandatory to teach [Indigenous content] in every subject? Yes,” Penny says. “But are all teachers incorporating it across every subject? I doubt it.”

A Collective Decision

The inclusion of Indigenous content was not the only change to the updated curriculum. The many new elements reflect the ever-changing, fast-paced world that children are immersed in today, according to the curriculum website. Reading, writing, and math are still the main focus, but more attention is paid to the development of useful life skills like “collaboration, critical thinking, and communications.” The flexible-learning lesson plans are designed so that students will understand larger concepts instead of merely memorizing facts. The website also says the new curriculum was developed with input from over 200 teachers nominated by the BC Teachers’ Federation, the Federation of Independent School Associations, and the First Nations Schools Association.

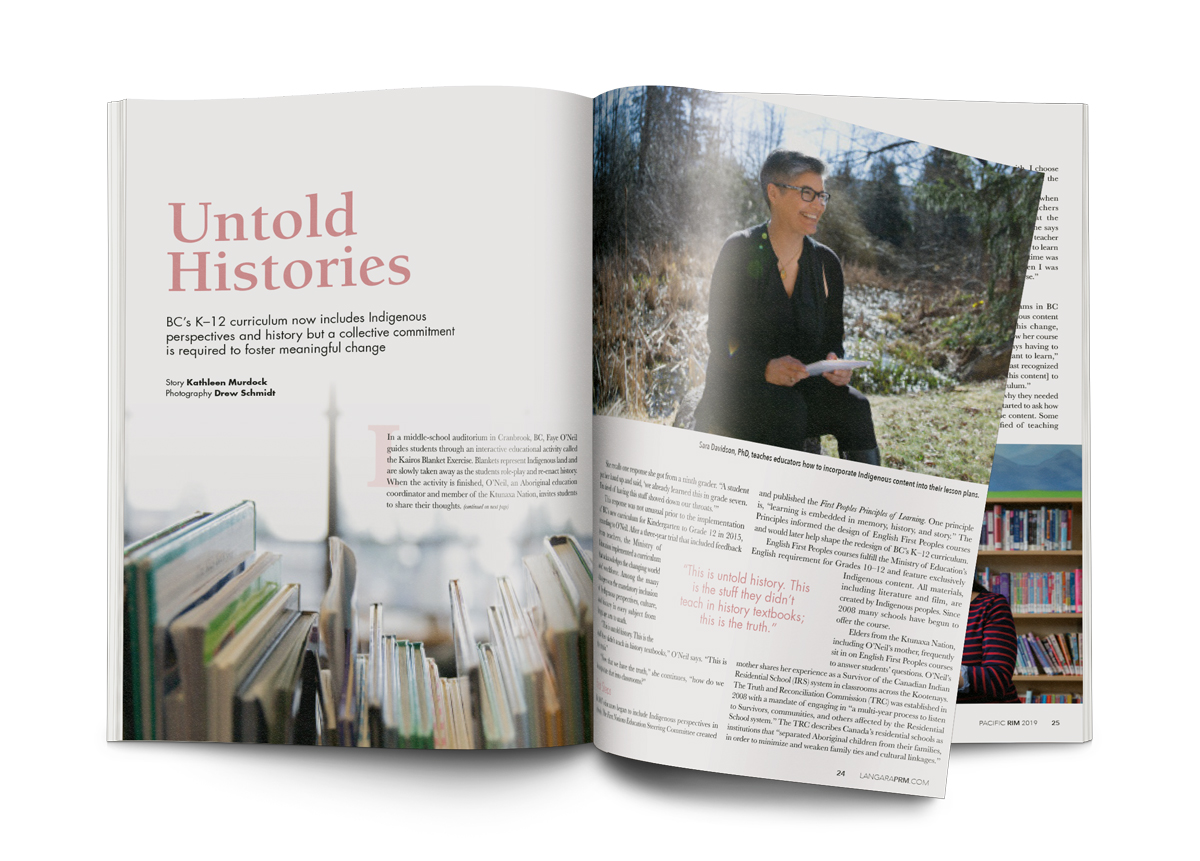

Sara Florence Davidson, PhD, says it is important for people to know that the curriculum was a “collective decision.” She says a common attitude she has encountered is that “Indigenous Peoples ‘made’ the curriculum change, and therefore we—as Indigenous Peoples—are responsible for providing education to teachers to help them teach this.”

Davidson is a scholar and educator of mixed Haida ancestry currently teaching at the University of the Fraser Valley. She has extensive experience helping teachers and teacher candidates bring Indigenous content, perspectives, and pedagogies into their classrooms.

“As Indigenous people, we have a choice about how we are going to engage with this,” Davidson explains. “We should [never] be pressured or directed to engage in a way that we are uncomfortable with. I choose to do this work because I believe in the importance of contributing.”

Before the curriculum change, when Davidson taught prospective teachers Indigenous education courses at the University of British Columbia, she says “there was a lot of resistance.” Many teacher candidates would ask why they had to learn Indigenous content. “A lot of my time was spent defending the course when I was actually [there] to teach the course.”

A Shift in Perspective

Teaching certification programs in BC made the inclusion of Indigenous content mandatory in 2012. With this change, Davidson noticed a shift in how her course was received. “I wasn’t always having to defend why it was so important to learn,” Davidson says. “People at least recognized that they needed to know [this content] to engage with the new curriculum.”

Rather than question why they needed to learn it, many teachers started to ask how they could incorporate the content. Some “expressed feeling terrified of teaching the content for fear of doing it wrong,” Davidson says. She says that it is fair for teachers to have concerns about bringing Indigenous knowledges into their classrooms respectfully. “It is important to recognize that there are protocols involved with Indigenous knowledge,” she explains. “However, their concerns should not be paralyzing.”

“It’s okay for teachers to let students know that they don’t have all the answers. Teachers need not position themselves as experts,” Davidson explains. However, she says, “it’s important for teachers to stretch themselves, because they ask students to every day.” Davidson recommends teachers first ask themselves about their own unique position in relation to Indigenous Peoples, and then how they can bring multiple perspectives into the classroom. “How do we connect with … local communities and local Nations … and do something meaningful,” Davidson says, “instead of just appearing to do the right thing?”

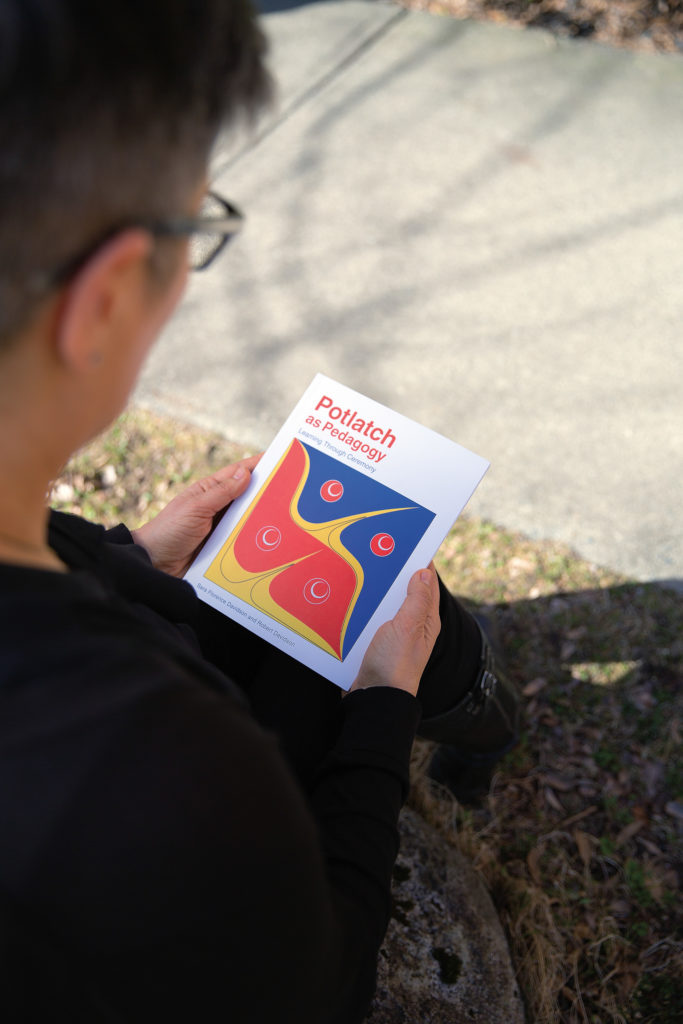

Davidson’s experiences inspired her book, Potlatch as Pedagogy: Learning Through Ceremony, which she co-authored with her father Robert Davidson. She says that the book can help educators “honour the culture,” rather than “make a show of integrating it into courses.”

Davidson hopes to see teachers use the First Peoples Principles of Learning in the current curriculum as “an opportunity to transform their approach to teaching,” rather than viewing the Principles “as a checklist.”

O’Neil agrees that inclusion of the Principles, and Indigenous content in general, “is about more than just checking off a box.”

“The Principles are for teachers to embrace, not just students,” she says. “Many have already embraced them into their daily lives.”

For Nancy Turner, an elementary school teacher in Surrey, the First Peoples Principles of Learning are part of her daily life. “I connect with them,” she explains. “Teaching the Principles is just good teaching.”

Turner only knows the new curriculum. When she began teaching five years ago, she had the option to teach the former curriculum or the new one while it was in its trial period. She opted for the new one because she believes it “sets children up for success.”

“We are living in a time where content is everywhere. We need kids to engage and reflect on content rather than just find and memorize it. We don’t want to just teach about history,” she says, “we want to teach them how to learn from history.”

Turner learned little about Indigenous culture and history as a child. “I never want kids to walk away not knowing Canada’s true history like I did,” she says, “because that’s not okay.” She also wants her students to know that Indigenous history impacts the present, and the issues Indigenous Peoples continue to both struggle with and show resilience against are “ongoing and not just of the past.”

Changing Relationships

Davidson hopes that the new curriculum will challenge stereotypes and lessen the racist attitudes many Indigenous youth encounter every day. She thinks that the changes within the curriculum may help Indigenous youth feel that they are seen and that their contributions are valid.

When she was in school, Davidson says she does not remember any educator holding up a book and saying, “‘this happens to be written by an Indigenous author and it is amazing.’ I internalized the view that Indigenous people did not have strong authors and that [we] could not write amazing books,” she says. She hopes that allowing students to experience “amazing literature by Indigenous authors” will “start transforming perspectives.”

Davidson recently spoke with a teacher who will teach the novel Indian Horse, by Indigenous author Richard Wagamese, in their English course. “Indian Horse being taught in a non-First Peoples course is really exciting,” she says. Blending Indigenous and non-Indigenous content recognizes our shared history and honours the contribution of Indigenous Peoples. As Davidson says, it is a step toward “creating partnerships and moving forward together.”

According to the TRC, for reconciliation to happen there must be “awareness of the past, acknowledgment of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.” The new curriculum is a small step toward healing and repairing relationships through education, but increased awareness and mutual understanding must be a priority. According to CBC’s website Beyond 94, which provides up-to-date status reports, only 10 of the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action have been fully implemented. We must make meaningful changes to create respectful relationships and address the past, present, and future.

“I have to believe that people who have accurate information and knowledge about history will change the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people because of the work that I do,” Davidson says.

Faye O’Neil acknowledges the importance of the inclusion of Indigenous history in the curriculum. “It’s in writing,” she says. “It’s there; it can’t be washed away.”